[Forthcoming in Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, 32(5), 2027.]

Intro

To write about something as fast changing as generative AI is to know for sure that much of what is written will soon appear obsolete. The issues covered will have either turned out to be non-issues, or they will have retreated from sight as all-too-obvious problems that should no longer be introduced as novelties. To write is to reckon most of the time spent will soon feel like wasted effort amid so much AI-innovation and AI-prospecting. Authors might fear that they were merely filling up the annals of bespoke journals such as AI & Society. All-too-quickly after publication their work will be viewed as addressing ‘yesterday’s problems’ and citations will soon diminish to nothing. In such a context, it might be possible to resource oneself into thinking these words are records of a moment in time. Here would be their value as testimonies when their ‘scientific’ value is short-lived. Namely, in year X this was how an author felt, this was how they viewed an AI-mediated world that quickly vanished from sight as it was replaced with a differently AI-mediated existence. This, at least, would be one possible justification for the lasting significance of observations and papers that might otherwise be considered bygone. But the fear that almost all reflection is soon enough passé, unutilisable, should not be shrunk from so fast. It could indeed be that the sensation of becoming obsolete, of only having the option of squandering time (in AI-related concerns, at least) is itself the most instructive element of this feeling. Obsolescence, wastefulness, might be welcomed, not treated as objections or reasons for embarrassment.

In this two-part essay, the recent development of generative AI will be recounted first in order to explore the multiple ways in which generative AI renders its users and their ways of seeing obsolete. The remit in this first section is fairly broad in order to indicate the extent to which obsolescence confronts subjects as an immediate problem rather than as the condition of the out-dated, retired, or aged. In the second part, the paper outlines an alternative approach to the problem of obsolescence. Here it builds on the work of Georges Bataille to suggest how obsolescence might be reframed and redeployed, considered now as a form of excess, or waste, in Bataillean terms. As such, the pursuit of obsolescence might be associated with the twin aims of remaining ungovernable and un-coopted. The paper presents the idea of ‘immediate obsolescence’ as a worthy aim, considered as a limit point, where acts are attempted that are already defunct.

Part One. AI and obsolescence

As generative AI has spread, multiple points of potential obsolescence have become manifest, placing a question mark alongside those human activities and operatives whose role and function must either be adjusted or whose position has been rendered defunct. AI has foregrounded and multiplied obsolescence points even raising the spectre of its own extinction as yet another possibility to be avoided. This section explores these multiple challenges and their interaction by considering the following major categories of the obsolete in an age of AI: (i) obsolete frameworks, (ii) obsolete creativities, (iii) obsolete fears, (iv) obsolete humans, and (v) obsolete AI.

(i) Obsolete frameworks

As a fabrication technology, AI functions by repeating and playing on established frameworks for writing and visualising the world, doing in each case what might be expected for each respective form of representation. Despite reinforcing dominant frameworks, AI perturbs each mode of representation it imitates by demonstrating how predicable a style or form can be. If news anchors can be easily replaced by AI-readers, for instance, this might well indicate how bot-like (over-determined, restricted) news anchors were before their replacement (Levy-Landesberg and Cao). The same goes for all other cultural and institutional forms that are currently being fed into an algorithm, including the academic paper, grant application, and student essay. AI raises the question of how it can be that these forms of writing were so readily available to synthesis. It may certainly prompt a degree of apathy, can make communication feel ‘meaninglessness’ when AI use is suspected, and may invite disillusionment about the standards underpinning these replicated artefacts (Winter, Hancock and Eisma). AI also places a very tender question mark over the assumed ‘humanity’ and originality of expression that each form of address was presumably able to transmit before its automation. Meanwhile, a cluster of more immediate consequences will be felt, for instance: (i) creative and intellectual outputs that can be reliably achieved by AI may be considered redundant even if AI has not been used (here obsolescence-avoidance means asserting the ‘added value’ and the ‘differential quality’ of the human input to avoid the claim of redundancy); (ii) authenticity of expression may increasingly depend upon not sounding like what AI has been trained to simulate (here avoiding obsolescence means avoiding coming across like AI, an investment of effort that necessitates familiarity with and avoidance of what AI has made tokenistic); (iii) those wishing to obscure their reliance on generative AI to write a paper or essay may need to introduce more human ‘foibles’ and inconsistencies into their work in order to avoid detection, whilst those setting essays may need to increase the demands an essay makes on forms of ‘personalisation’ which will now carry a higher premium than, say, clarity of expression or apparent mastery of subject matter (i.e. in this case working against the essay’s obsolescence involves recasting the activity of essay writing so that it can benefit from but also exceed the kind of assistance that AI provides). Evidently, the frameworks for writing and visualising the world under scrutiny here are not immediately rendered obsolete by AI (AI functions by making them persist), and yet, obsolescence returns within the enactment and negotiation of these forms of representation as a persistent concern, as a recurrent prospect to be repeatedly avoided and renegotiated.

To indicate another set of dynamics by which frameworks of representation have been shaken and have demanded efforts to actively maintain them, it might be noted how, in response to AI’s increasing adoption of the role of arbiter of truth and human expression, and in a manner frequently likened to an arms race (Chatterjee and Fernandez; Chow and Perrigo; Stening; Taher; Lyu), various truth-guaranteeing technologies such as digital watermarks have been developed so that a photograph of an atrocity, for instance, can be confirmed as true. Attempts have also been made to limit or regulate the spread of AI into areas where veracity and good practice is a thing to be strictly guarded—investigative journalism, healthcare and juridical systems, for instance (Munn, Magee and Arora). Safeguards have been introduced and algorithms have been to an extent ‘socialized’ to refrain from offering harmful advice or against appearing overly sentient. This work has attempted to reassert the validity of the frame. Meanwhile, considerable effort has been expended in training AI to observe the basic rules of the frameworks it is necessarily also perturbing. Namely, after the initial internet scraping and the development of the basic algorithm, AI training proceeds via an obscure process outsourcing tasks to workers who are asked, inter alia, to classify images in order to train image recognition algorithms (labelling heads, and knees, and elbows in a picture of a crowd, for instance), rank AI responses to given tasks (conversing for several hours a day with AI on all and sundry topics), write better responses in specific genres or areas of specialism, again to train the algorithm (up to $300 for a Socratic dialogue, apparently), clarify edge cases (the woman wheeling a bike killed by a self-driving car because she was neither ‘pedestrian’ nor ‘cyclist’), and classify extreme, disturbing, and depraved content, both textual and visual, to train the algorithm so it may better identify and filter out such material from its generative work—most often without safeguards or adequate support (Perrigo; Dzieza; Blum). Yet, despite such efforts to make AI safe and truthful (or less flagrantly dangerous, less prone to error), engagement with the world, at least digitally mediated engagement, has been irrevocably changed merely by the knowledge that fakery is rampant, easy, and cheap. This need not announce an epistemic apocalypse (Habgood-Coote), but it does introduce a degree of scepticism and detachment into social and political life which many would consider dangerous (Yadlin and Marciano). The frameworks through which reality is constructed have become questionable if not detached from what reality once was held to be (Söffner) and relationships to the truth have arguably become more fluid.

(ii) Obsolete creativities

Those working in the creative industries are facing an existential crisis of their own, an “emerging ‘creative precarity’: that is, cultural workers’ increasing lack of control over their distinct identity, roles and rights as a ‘creative beings’” (Lee 1316). Script-writing, to take one example, will now be at least part automated (Bedingfield). Professions including programming, copywriting, and journalism, are also said to be under threat with those involved facing the prospect of a skill-set becoming progressively obsolete (Castelvecchi; Williams; Bruni). But the problem is far wider, with workers in almost all fields reduced to, or at risk of reduction to becoming mere ancillaries of a “cybernetic regime” (Vachnadze). One response has been to emphasise the human element in creative production, and so mount a defence based on what is considered inviolable, what cannot be simulated, in this kind of work (Hutson and Schnellmann). And so, to the extent a creative activity can be shown to be the product of human experience and human interiority, or carries some kind of ‘soul effect’, it will be redeemed and designated as authentic. AI can achieve none of this, its critics venture. Its outputs may be mistaken for ‘real’ artworks or fruits of the intellect, but they can be destroyed instantly by the decisive statement—this artwork, this intellectual piece, was the product of generative AI. That statement alone will immediately collapse its illusion of human depth or substance, so it is hoped. Or it ought to, for this presumption concerning a collective taste for authentic art, and a distaste for AI-generated art has become yet another testable hypothesis in the growing side industry of AI research. Apparently, some art appreciators find AI art compelling too (Demmer et al.).

Until the point of its denouement an AI generated work of art has engaged in trickery—its critics maintain—it is a simulation, a forgery, and a betrayal of what art has been and might again become. Even artistic movements which questioned artistry and authorship such as Dada and Surrealism—with their idiotic pronouncements at an idiotic world, excessive performances, absurd proclamations, and automatic writings—were still able to express a shared sense of crisis, a perception of the limits of civilization, the horrors of industrial society and industrial war. If Dada is to be understood as the expression of “a collective melancholia, mad laughter, revulsion, and rage” (Wenaus The Literature of Exclusion 15), this revulsion cannot be simulated. Contemporaries will need to resource themselves from their own rage and be differentially perturbed. This does not exclude the possibility of some (neo)Dada-AI encounter, but there will have to be some kind of cost, or damage done to the latter (or both). Meanwhile, a ‘surrealist’ image generated from some command prompts and a database of similar images simply cannot connect with the political and emotional tumult of the period from which the movement emerged. Even an accidental artifact, a variant of “jackrabbit surrealism” (see below) produced by AI trained on its own datasets, is computational nonsense, rather than the effect of a political moment. AI cannot creatively rethink ‘surrealism’, either, or resituate it in the very different context of the twenty-first century. It is imitation without terror, with no sense of urgency, with no connection to the fathomless work of the unconscious (so-called), the tumults and passions of the human interior (as they were felt), that once provided art with its stimulus. An AI bot might be invited to write like André Breton, and the thing will get on with the job. The bot will not receive its question and simply answer no. It will only say so if invited. Tell me this is a bad idea to write like Breton, and tell me it as Breton would, might be the input. And the AI bot, quoting Breton (perhaps) might say something like, “Unfortunately, I’m largely forced to decline giving an opinion” (Breton Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism 241), or, “You ask too much of me!” (Breton Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism 245), or, “It’s precisely a steady diet of such questions that will be the death of us” (Breton Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism 213), or some muddled up version of all three, which would still be too gentle, too bland, for it would not carry his anger, or his wit.

And yet, attempts to defend human creativity against AI-incursions often insist on the human element of such work and so due caution is required here. The defence against obsolescence again focuses on human weaknesses, where it is said that human beings, unlike AI, experience cognitive dissonance and inner conflict—ethical, intellectual, emotional—which art and intellect become an expression of. This troubled human element will remain in demand, so to speak, even if it can be hard to tell the difference between the artefacts produced. To take a prominent example: having been emailed AI-generated lyrics “in the style of Nick Cave” (apparently this happens quite a bit), the artist declared that they sucked. Here was another clear case of “replication as travesty”, wrote Cave (Christchurch).

Yet when ChatGPT started fabricating titles, indeed entire blurbs for books I had never written, I myself wondered if they might indeed be worth producing, and so whether I should write Philistine, a “dark satirical novel that delves into the world of art and academia [that] revolves around a disillusioned academic who becomes embroiled in a plot that questions the value of art and academia”. Or if I should write Nonscholae, a novel in a similar vein, yet “noted for its metafictional elements and philosophical enquiries”. At least I would have suffered in producing them, which is Cave’s point:

Songs arise out of suffering, by which I mean they are predicated upon the complex, internal human struggle of creation and, well, as far as I know, algorithms don’t feel. Data doesn’t suffer. (Christchurch)

These are, perhaps, fairly ordinary claims for art. But Cave goes on to develop his conception of suffering to include limit experiences and a kind of “self-murder”.

ChatGPT has no inner being, it has been nowhere, it has endured nothing, it has not had the audacity to reach beyond its limitations, and hence it doesn’t have the capacity for a shared transcendent experience, as it has no limitations from which to transcend. ChatGPT’s melancholy role is that it is destined to imitate and can never have an authentic human experience, no matter how devalued and inconsequential the human experience may in time become.

What makes a great song great is not its close resemblance to a recognizable work. Writing a good song is not mimicry, or replication, or pastiche, it is the opposite. It is an act of self-murder that destroys all one has strived to produce in the past.

Cave’s defence against AI is worth paying attention to. It focuses attention on art being one possible conduit through which a subject is transformed so they come to see or experience what they could not have experienced or would not have seen before embarking upon this or that creative work. The artist has migrated via what Cave calls ‘self-murder’ to the coordinates of a different, or at least, a slightly displaced, personhood. This is a journey that LLMs (large language models) and generative AI cannot experience. Cave’s analysis contrasts to other similar-sounding defences that assert the place of suffering, of authentic experience, but which really wish only to assert the value of the musician as a unique commodity. For instance: however good AI generated music might become, “[w]hen it comes to music, people enjoy connecting with the artists’ stories as much as they appreciate the songs themselves” (DeVon). Consumer taste, reconfigured now as the humanity of an audience, is elevated to become the decisive factor which will save the artist from replacement. In one possible scenario, human-made creative outputs will simply command a premium in certain markets due to their envisaged authenticity (Cremer, Bianzino and Falk).

(iii) Obsolete fears

For some critics, the realisation that many human notions are obsolete is a late one. This would make many obsolescence-related fears atavisms of a kind. Those who might be considered (or might consider themselves) ‘better equipped’ to cope intellectually with the arrival of generative AI, have come at the problem with all the theoretical equipment they already had in place before AI became mainstream, as if 20th century literary theory and philosophy was merely a long series of preparations for this moment. Perhaps among the first wave of gen-AI criticism, this will be a characteristic response, where the reader is told that Baudrillard, Serres, Virno, Foucault, Deleuze, etc. etc. already had it figured and had already pretty much thought it all through. These gen-AI critics need only restate their arguments.

It has been pointed out, for instance, that humans have always been technological beings shaped as much by their tools as they have vested those tools with their intentions. Yes, AI will change how texts are produced and may influence how thought is constructed, but it will not fundamentally disturb our being which has always been technologically constituted (Coeckelbergh and Gunkel). As such, it even makes sense (or so it has been argued) to ask how AI might be ‘improved’ so that it better interpolates human subjectivity as, say, Foucault theorised it (D’Amato). Rather than ask after the ‘humanity’ of generative AI (which would be a non-problem, a submission to defunct humanist notions), we had better ask how generative AI might model “Foucault’s self-conducting subject, a subjectivity always-already embedded in a continuous political and social contestation”, by becoming a better attuned “self-conducting AI subject”, considered to be similarly embedded and distributed across networks of power and discourse (D’Amato 1638).

In response to the fear that control over language is being relinquished to the algorithm, it is observed that the arrival and profusion of large language models which write in ‘real time’ merely prods an unsustainable Western conceit, namely, the idea that language could be a mere instrument of human intention. Or the notion that conscious mastery of language was ever possible, as if a writer with a pen, or a typewriter, or a computer, once sat down and wrote in a condition of magisterial isolation. Language has always had some degree of ‘agency’ in this process… if the term even applies (Coeckelbergh and Gunkel). It has been argued, in turn, that generative AI usefully and necessarily again challenges enduring conceits of human authorship—the idea that a specific individual must be made responsible, creditable, blameable, accountable for each text—and will help to switch emphasis and interest from the so-called genius of creation to the work that is done at the other end, by readers, listeners, viewers, and, now, ‘users’. The final ‘death of the author’ has been welcomed and with almost unqualified enthusiasm by critics who appear to view almost any form of artistic agency (which might be described as betraying artistic ‘genius’) as being necessarily enslaved to the needs of capitalist accumulation (Fabrocini, Terzidis and Chen). These arguments effectuate a kind of re-run and revision of those once made by Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault (Barthes; Foucault “What Is an Author?”). It is as if their intuitions will finally be allowed to bear out. Texts are now produced that have no identifiable author, and these texts draw from a vast reservoir that cannot be attributed. It is as if the ‘author function’ (Foucault “What Is an Author?” 211) [the construct which fixes the author in place as the originator of a work and guarantees the authenticity of a work by its attachment to a named individual] will finally be allowed to disappear in a profusion of texts that can no longer be authorised and so have been liberated at last from this constraint. It should not matter how the artwork is produced—by a human, by the algorithm, or by some combination of the two—if its appreciation, its creative re-interpretation by audiences and readers, is the paramount concern and locus of activity (Arielli).

Still another line of approach is to make a case for the role of artificial intelligence in the creative process, and this approach is likely to become ascendent: creators will, already do interact with AI and use it as a stimulus, even as a pedagogue, with AI coaching against predictable syntax, for instance, or used “to filter in only those statements that suggest a sparkling wit or erudition” (Booten “Flusser’s Demon: Writing under the Eye of an Automatic Critic” 16), or to simulate the conflicting responses a student might receive at a creative writing workshop (Booten “Lotus Chorus Workshop: Designing for Cognitive Overload”). Figured in this way, generative AI merely augments an already existent set of creative and intellectual practices—it (and they) are presented as less alien, less completely novel, than might be feared (Hutson and Schnellmann).

(iv) Obsolete humans

These debates pale somewhat against more urgent dangers such as the widespread propagation of medical misinformation (Monteith et al.), for instance, or the switch to AI-driven recommendations in end-of-life care (Balasubramanian et al.). That a GPT-3 powered medical chatbot, admittedly in its development phase, told a mock patient to kill themselves (Quach) hints at a future in which the algorithm might decide that humans, some at least, are a burden it could do without. Or perhaps more likely, it suggests a future in which AI simply won’t factor people (or their wellbeing) into its calculations and will marginalise them as a consequence of its power-seeking behaviour, leading to human disempowerment and possibly extinction (Dung). This is one of many possible scenarios of an envisaged AI takeover which have already been described (Bales) and, consequently, will have taken up residence on the internet ready to be scraped (meaning that AI can now describe its envisaged takeover, like it describes everything else, with complete indifference).

But already in its current form AI has been indicted for paving the way to a “full-on algorithmic authoritarianism” (McQuillan 3), for facilitating “violence at scale” (Ricaurte), and for posing existential risks even to an utterly servile, enslaved humanity (Bucknall and Dori-Hacohen). AI has participated in its first genocide, with its use by the Israeli military to facilitate mass targeting and bombing of an intensity that a campaign superintended and signed off by human operatives would not have managed (McKernan and Davies). There is, too, considerable potential in the form of lethal autonomous weapons, with autonomous drones already operating in Ukraine. Everything is in place for the widespread adoption of cheap, weaponised drones, perhaps operating in swarms and driven by facial recognition technology (Keating; Emerson and Nieva). This future AI may not necessarily be advancing all that much in its inclination for destruction and its ethical deployment beyond that of its makers. More efficient and decisive, for sure, and differently grotesque, but still faithful to the model which underpins the AI boom, one in which generative AI can only (for the moment) churn out what it is fed with (even if by multiple re-feeding it migrates to ‘new things’).

Again, the chief question becomes one of how to introduce safeguards, how to limit or better regulate the technology (Adam). In technical terms, this is known as the alignment problem (Kasirzadeh and Gabriel; Han et al.; Christian)—the conundrum of how to orient AI to so-called human values. This problem is posed seemingly without embarrassment, as if human values or their failure to humanise were not already at issue.

One of the more remarkable suggestions in this literature is that AI systems themselves would need to study human behaviour and so develop their own ways of modelling human values in action. This is because AI systems are dynamic and ever changing and so could not be encoded with a single and stable value set or set of instructions or principles to abide by. Such thinking also reflects, in anticipation, a near future in which existing value frameworks become obsolete too, as AI changes the overall landscape of behaviour.

To ensure human misbehaviour remains unobserved by AI value-building algorithms, the supervisory task would be assigned to supplementary “AI guardians” given protected environments to train in, guardians that would subsequently superintend other AI. These human studies, conducted by AI, would be limited to observations made in those “stable contexts” (Han et al.; Etzioni and Etzioni)—itself a problematic construct, as if the achievement of human stability were not itself a consequence of human violence or constraint (where the achievement of human stability might be defined as the effect of discipline and subjugation with an exploited/excluded/eliminated other) (Mbembe; Foucault Discipline and Punish).

It is claimed that ‘users’ too must be educated to behave better when AI is watching so as not to teach the algorithm ‘bad things’ outside these controlled settings (Etzioni and Etzioni). All of which serves as an explicit admission that there can be no agreement (between humans) as to what ‘human values’ are, how they should be defined, and if they even exist as generalisable entities, let alone whether humans are capable of modelling them or can be trusted to interact with AI responsibly. The overwhelming impression is that AI development will simply muddle on, gathering up newly discovered concerns along the way. The call to regulate and safeguard will be a recurrent one.

(v) Obsolete AI

It would appear that AI has still not quite given birth “to a hermaphroditic monster capable of reproducing itself” (Armand 155), instead leaving to its users the role of intelligent beings. It has been repeatedly observed that AI lacks intelligence (Floridi), which would make the acronym the derivative of a misnomer, at least for a little while yet. Those who fear some kind of AI takeover might be gladdened by evidence of its persistent shortcomings, whereas those who know how much damage AI can produce in the hands of its maker(s) understand well enough the opposite. Either way, a transition appears to have taken place, into what has been described as the “indifferent, efficient, inhuman superidiocy” (Wenaus The Literature of Exclusion 14) of an algorithmically mediated world, a world in which “everything happens in a completely idiotic way, and with increasingly innocuous ease” (Wenaus The Literature of Exclusion 17).

Large language models present errors with the same performed, linguistic certainty, as they do truths. They issue responses that are factually incorrect or deviate from the input prompt, and yet the error-riddled text they produce may be disarmingly convincing and will contribute to the common lot of misinformation. This may well morph so-called generative AI into a degenerative analogue as the textual soup from which AI writes contains more and more of the data produced by its predecessors—the ‘unintelligent’ content we may still have the wit to laugh at. Although AI was first trained on human-generated text, this will soon change as the database fills with more AI generated content as past generations of AI effectively pollute the database from which future generations draw. This has been described as a form of self-eating (Manghani; Rao), although it might be closer to coprophagy. An eventual collapse of generative AI has been envisaged (Shumailov et al.) as a nadir is reached where large language models have become responsible for generating or helping generate the vast bulk of the text that is available online. This will become the text their bots continue to scrape, and which generative AI continues to cycle and further deteriorate. In one worst-case scenario, so-called high-quality data will have been diminished, and the era in which AI modelled itself on human speech and human writing, will be largely over.

Those who would reject this assessment have claimed that there are plenty of other sources of high-quality data—astronomical data, for instance, is enormously rich (Jones)—but the prospects for astronomical writing remain unclear. It might well be disappointing, this kind of writing, rather than unfathomable as the universe itself, and may not at all even begin to approach what Andrew C. Wenaus has claimed for “our duty”, namely to “expand language into, not a, but the cosmos”:

we must begin to plant new languages, to grow a universally emancipatory linguistic garden across the planet, and then allow our garden to grow and grow and hang from the sphere of the planet, to allow our vines to climb beyond the upper canopy of trees, and to float and waver like informatic kelp into the cosmos. (Wenaus “An Interview on the Crafting of the Infinite Metalanguage”)

This prospect imagined by Wenaus is not one of meaningless profusion, an expansive nonsense of fecund language generators. Or if it is meaningless, and nonsense, this will only be because ‘it’ (namely, an unfolding event composed “of words, glyphs, sounds for every possible object, concept, and relation possible to the point of infinity” (Wenaus “An Interview on the Crafting of the Infinite Metalanguage”)) expands beyond the grasp of human intellect and becomes something greater, perhaps divine. It reduces its human readers to illiteracy, it almost condemns them to illiteracy, and to the supposed awe and humility of the illiterate (…which may give the illiterate at once too much and too little credit).

By stark contrast, simulations of a future in which AI bots are repeatedly fed with their own outputs (and cannot benefit from so-called “astronomical data”) soon lead to the production of a different kind of nonsense, an impoverishment of sense. Notoriously, a Wikipedia-style description of 14th century church towers degenerated by the ninth generation of generative AI to:

architecture. In addition to being home to some of the world’s largest populations of black @-@ tailed jackrabbits, white @-@ tailed jackrabbits, blue @-@ tailed jackrabbits, red @-@ tailed jackrabbits, yellow @- (Shumailov et al. 758)

First the tails in a distribution are lost, meaning that low-probability events, marginalised and heterodox possibilities are extinguished. Then the central distribution begins to adjust until it no longer resembles the original data. Crucially, the new distribution, the source material from which the nonsense is probabilistically ‘written’, will have significantly reduced variance, and so the scope of the nonsense it has the capacity for is itself significantly narrowed as its capacity for nonsense is enhanced (Shumailov et al.). This is important, as it forecloses any possibility of escape (via nonsense) to entirely different landscapes of signification.

For now, the issue of AI-hallucination holds most attention. It continues to rile those who fear AI is departing from reality and would wish for it that AI would either be ‘corrected’ or held in check. This fear that AI might have already interfered with our ability to determine what is real and what is fake will predominate among those who represent ‘the realistic attitude’ for which André Breton long ago declared his loathing. According to Breton, this demand that the world must be made to make sense, that it must submit to human reason, is an expression of a blinkered outlook characterised by “mediocrity, hate, and dull conceit” (Breton “Manifesto of Surrealism” 6). As Breton saw it, this preference for an orderly ‘real’ is based on a foreclosure of possibilities the realist simply will not entertain. A hundred years since Breton published his first Manifesto, surreal images may be produced with algorithmic ease and hallucinations and automatic (machinic) writing can proliferate. And yet, the surreal imagery produced by AI is typically bland and tokenistic (floating orbs on flat landscapes, etc.), and when it comes to writing, AI will only be able to appear quirky based on its ‘understanding’ of prior attempts to write the unexpected. Only the non-sequitur, the break in logic an hallucinating AI achieves by failing to adequately synthesise, has disruptive potential, and not the content of what flows after. This content always returns to the norm (including norms of atypical writing) that AI is attempting to produce.

To prevent the feared “model collapse” and a projected exhaustion of available data, there is some hope that deliberate attempts to prioritise niche and eccentric data might keep datasets rich enough to continue to function, with even perhaps “public subsidies to protect [the producers of] ‘tail’ knowledge” [meaning, the oddballs, untapped specialists and other producers of ‘useless’ knowledge] (Peterson 3264). Or, it could be that AI might produce its own sufficiently rich synthetic datasets to train on, or finally, AI might be trained to do “more with less”, based on the observation that AI can improve its predictive facilities by re-reading the same dataset, and so re-studying the same material (Jones). There is the prospect that in the hunt for so-called high-quality material, pre-AI texts may be prioritised in AI-training, which could mean that AI-writing would be to some extent anchored in time by the resources it can rely on to ‘think’ and write with. This AI future would be one that would repeatedly index itself against the human-written texts that predate widespread adoption of the technology (circa 2022), as the first two decades of the 21st century continually resource all the thinking of the decades to follow. Or perhaps the 20th century might be considered more reliable, in which case all subsequent textual outputs would be, in a sense, stuck, endlessly cycling iterations of its linguistic achievements (in the manner of James Reich’s SF novel, Skinship, which literally reprints the textures of the 20th century in the last spaceship to leave a dying Earth (Reich)). At the same time, future human-AI interactions will themselves carry even more of a premium, used to sense check and recalibrate the algorithm as it wanders from its tasks. And yet, as users become more dependent on AI-facilitated thinking, the thinking processes they are able to deploy risk becoming immiserated or at least transformed into a new realm of algorithmically facilitated thought-potentialities. It is possible that these future users would not be able to adequately think outside their AI-depleted environment (Alexander). Generative AI seems tied into a mutually-reinforcing obsolescence loop, depleting its own raw material (its resource of ‘high-quality’ texts) and depleting the capacity of its users to produce more of that material without AI-assistance.

Part Two. Artifice and excess

Generative AI would appear to be embroiled in a complex relationship with obsolescence. This occurs via the production of multiple points of obsolescence in those human activities it is replacing, and through its own self-inflicted blows, the depletion of its own datasets. These are the so-called ‘tails’ of the datasets—the outliers and odd configurations—that keep those datasets ‘rich’ and mitigate against model collapse. There would appear to be a twin-demand here to favour the margins or the outliers: first, to maintain a functioning AI-system (the survival of AI would appear to depend upon it) and second, to protect those activities that AI might be threatening to occlude as it imposes its own simulations on human activity which have a tendency to favour the trite and banal. In the context of generative AI, the concept of obsolescence is evidently a difficult and ambiguous one, given how the prospect of obsolescence may be constructed as a both a threat (to human activity to AI survival) and a source of opportunity (to maintain an existence against or in the context of AI). And yet, in its very ambiguity the obsolete might be brought into conversation with another similarly ambiguous concept, that of excess, understood in the Bataillean sense. If obsolescence, like excess, is inevitable, the challenge becomes one of how to expend it. Bataille’s answer for excess might apply to the obsolete, namely, that it is preferable to expend each unproductively. Both excess and obsolescence are, from this point of view, to be indulged, not remedied. The following Part Two will explore this association beginning with a discussion of excess in the context of AI.

(i) Excess and AI

Rather than treat AI and its large language models as a problem in need of restraint, or as technologically/ethically deficient and in need of correction, these technologies might be theorised in their almost immediate excess. This follows from Bataille’s concept of “general economy” (Bataille The Accursed Share, Vol.I) and his attempt to reorganise economic thinking around the problem of how to deal with excess energy in all its forms, a surplus, a redundancy that will always attend human existence however parsimonious, considered, or orderly it might hope to be. The challenge, for Bataille, is not to reduce or redeploy this excess (the conventional logic of sustainability and reason) but to become better at expending excess energy, to embrace a certain profligacy, or recklessness, as this energy is released without return. At first sight, this call to indulge excess expenditure in the context of AI (let alone any other context) might appear entirely wrongheaded, given how one of the chief indictments against AI relates to the vast amounts of energy AI is already consuming in its data centres (Milman). Bataille’s approach is nothing if not counter-intuitive.

Bataille levers his thinking against the logic (come to dominance in the period of modernity) that understands economies in terms of the seizure of resource and the management of use (or how to instrumentalise time, or rationalise effort, get the best return in a given situation, and so on). For Bataille, these efforts will always let something slip through their attempts at containment, this is the excess, the non-utilizable excrescence, where Bataille’s wager is that such energies will wreak even greater destruction if a sufficient outlet is not found and built into the rites, the erotic and sacrificial concords, of a given culture. All the efforts to restrain and instrumentalise, to seize and manage, are undoubtedly violent in their own way, but they will be ripped apart at intervals by forces that will always be beyond their control.

Bataille begins his analysis at a celestial level, and posits that this excess energy, which will always be produced, and which no human civilization will succeed in fully instrumentalising, originates in the solar energy which drives all processes on earth. Past cultures knew how to expend this effervescence passed to them through the gnawing and extruding energies of the biosphere and the streams, oceans, and clouds that fell upon their lives in a ceaseless condition of unrest. They gave up these excess energies that they themselves also (and by turn) extruded, and did so with comparative safely in feast days, sacrifices and games, and then somewhat later in the construction of obscenely costly and useless carved edifices, the medieval churches, which could not be appreciated in all their lofty detail by those congregating below. These churches were in their upper tiers and ornamentation merely, largely, to the glory and sight of God—that was deemed sufficient to justify the workmanship. Bataille gives other examples too—most notably, Sun-worship and human sacrifice among the Aztecs, as well as potlach—but these examples require considerable and careful explication. To stick with the medieval church edifice for the moment, and to understand just how odd this kind of sumptuary construction of great edifices would strike us today, Bataille imagines “a structure in New York devoid of practical purpose or commercial value: it would tower over the skyscrapers like a church over the houses of a little village; it would be lavishly decorated even on parts of it that could never be reached” (Bataille The Limit of the Useful 63). Modern civilization has no comparable outlet for its excess energies and is reduced to expressing them as art installations (Hawkins). There is nothing it could permit, no extravagance it could imagine on the scale of its cycles of production and consumption. Everything will have its utility, even if this utility is to be found in its non-utility (the extravagance that is invested in housing artworks in public galleries, for instance, will be variously justified in terms of its societal benefits, by each quota an artwork uplifts the soul, humanises or educates the spirit). Via its preoccupation with the usefulness, even the counterintuitive usefulness of useless things, modern society has obliterated from its perception the value of wasteful expenditure, of indulging activities which cannot be justified or reclaimed. If wasteful expenditure still exists in pockets of activity, it cannot be communally enjoyed. It will have been privatised and sequestered and might only be admitted in public accompanied by an apology or an excuse. For this reason, modern society is destined (in Bataille’s assessment) to dispense with its excess energies catastrophically, in ecocides, holocausts, and wars.

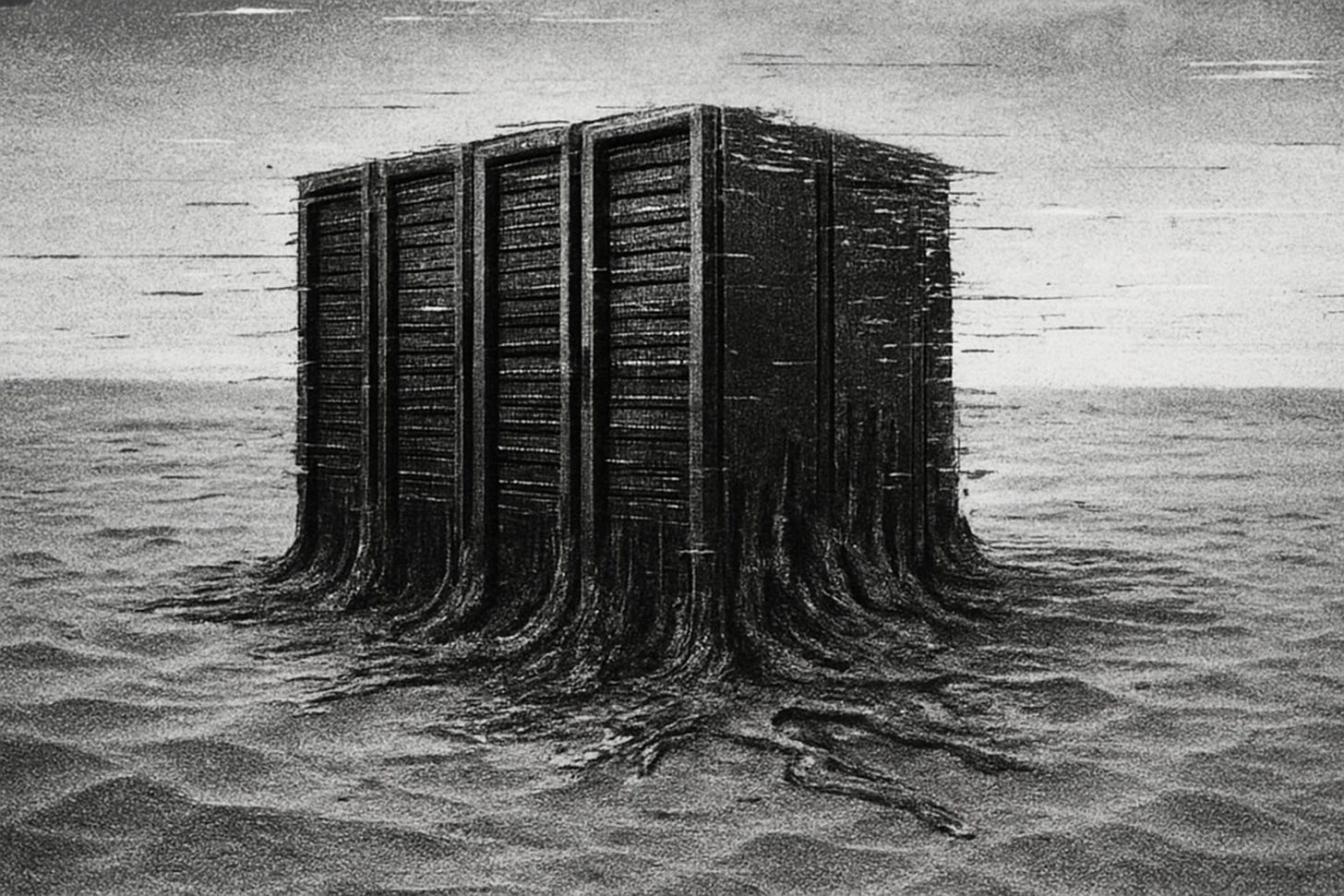

Work on Bataille’s general economy has seen a resurgence of interest. It has been used to re-interpret the nature of financial crises (Crosthwaite), to argue for the overall economic benefits of rich nations giving away their surpluses without condition (McGoey), and has been applied in an effort to reorient sustainability practices from efforts to manage scarcity to the problem of how to better engage the inevitable excesses and wasteful expenditures of human existence (Stoekl; Kendall; Huling). AI might be conceptualised in similar terms. Its data centres have a clear enough imprint. They can be located geographically and their physical contents described and itemised—a full inventory is possible—yet they facilitate a highly amorphous computational soup in which AI exists as a vast digital excess, circulating globally, growing and transforming constantly, located in no particular place and able to be deployed everywhere at any time. A crucial question for Bataillean philosophy then is whether AI-outputs might be conceptualised in this way as form of wasteful excess or “unproductive expenditure” (Bataille The Accursed Share, Vol.I 136). In the era of generative AI this waste comes both in the form of rejected text (AI text not adopted or put to use), and the vast energy and resource consumption that running AI systems requires and expends. This possibility, wherein AI is prodigiously wasteful and bares analogy to Bataillean excess, must be set against the rival interpretation, which might argue that although the (fossil, nuclear, and solar) energies used by AI are ‘wasted’ (these energies cannot be reclaimed), AI has the ability to recycle or repurpose its other major waste material, which is textual. AI may use the majority of its excess outputs (those rejected by users) to train its systems, thereby consuming (at least some of) its own excreta. This ability to recuperate potentially ‘everything’ with a digital trace is concerning, given that anything which leaves a digital residue (as most human activities now do) may be absorbed and cycled as AI training material.

These are difficult questions to answer empirically, for a number of reasons: AI operations effectively take place within a black box (they cannot be inspected); AI developers are notoriously reluctant to divulge what data they train their algorithms on; the broader development work behind generative AI is shrouded in secrecy (even the extent of the global workforce currently employed to train AI is unknown); and the future of AI remains uncertain (Jones; Bucknall and Dori-Hacohen). It is necessary to enquire instead after the conceptual repercussions of each option: Namely, (1) what might be the positive implications in Bataillean terms if AI is indeed truly excessive insofar as it produces too much material even for AI to put to use and productively employ. Or, alternatively, (2) what might it mean if AI actually tends toward closed systems where excess is recycled as raw material? This paper can only begin to address each possibility.

(ii) New ecologies of excess

The experience of AI has certainly been one of excess. As soon as they emerged, generative AI tools were already too much. They produced too many problems, developed too fast, expanded too quickly and inside too many different domains. AI development was something that needed to be paused, as industry figures were claiming back in 2023 (Paul). AI was already outpacing regulation even understanding of its capabilities. But the AI boom was also built on excess. This was the already-existing digital plenitude which made generative AI possible or was indeed its condition of possibility. Generative AI was designed as a tool for dealing with too much data, for feeding off excess and returning it to use. This excess took the form of petabytes of data distributed online and gathered by internet scrapers that were documenting the internet long before doing so would become so lucrative. It was a vast resource that was hitherto beyond scope. Attempts could be made to mine it for useable information, but only after the arrival of generative AI could such vast quantities be digested at speed.

Much of this data was old or static—dead texts by dead authors, almost never revised Wikipedia pages—but the rest might have been considered ‘living’, or derived from something close to living, as traces of selves which continually shed data online. Generative AI could only make its appearance by drawing resource from this bio-digital environment that was already providing the connective tissue in subject formation. There was, in other words, an excessive or excess-producing investment in an online world that had carried into its realm that older transformation which had rendered the ‘confessional self’ (Foucault The Will to Knowledge) into an operable, manipulable presence. The self that Michel Foucault describes (which tortures itself as it divulges/constructs its ‘inner’ secrets), was transported into a compulsively, obsessively, self-disclosing being, perpetually tied to its online identities or projections.

This bio-digital tissue grows via a vast expenditure of hours spent doomscrolling, liking, swiping, and maintaining a presence or an existence against ‘inactivity’. AI derives itself from these habits and their traces, from an epistemic regime which put these selves (never discrete, always-already networked) into repeated circulation, rendered as data, nudges, prompts and adjusted behaviours, a hitherto untappable if not eminently manipulable ecosystem. The very extent to which users willingly divulge themselves textually, visually, and then again divulge themselves further when interacting with (and thereby training) new AI technologies, must be considered the very basis of this ebullient force, this living pressure, which is furnishing the system with its data and driving its development.

The excess that generative AI derives its power from was, then, a vast resource which, up until the point of its introduction, could not be put to use in a manner consummate with its nature. This vast soup might be studied for patterns, or trends, and used as a resource to predict consumer behaviour, for instance. But only with generative AI could it be put to work in a manner that would not just mine but inhabit its raw material—all human thought and activity as it has been recorded and made available online—and manufacture more of the same, with adjustment. In this respect, generative AI has become the most powerful tool for putting human excess back into circulation. It draws from this excess—all the fragile, intemperate, passing utterances which should have been beyond co-option and use—in order to produce more of the same, or at least, more ephemera of comparable status. And as it produces its own subsequent excess—all the prompts, interactions, all the records of accepted and discarded AI-generated visuals, sound and texts—this excess too becomes part of its training material.

Print cultures—those which have continued to look down their noses at digital ephemera such as social media posts and blogs, were differently co-opted. Their materials had to be transformed back into a living or at least circulating excess that the printing press and the typeset were designed to kill off. This is something writers can well intuit—a work is dead to the writer once it is published, or as Walter Benjamin once put it, “The work is the death mask of the draft” (Benjamin 70). Those campaigning for authors’ rights have been suitably appalled by the arrival of generative AI and the first reports of what it had been fed with (Veltman). Their texts had been unmoored and placed in circulation in defiance of the habits and expectations of print culture, which assumes that when a text is eventually published, it will be fixed in its final arrangement and respected as such. Nothing is fixed now, in textual terms. This is not the same as saying that anything is possible—texts are still organised probabilistically and to the expectations of a particular form or style. But it would seem that traditional print cultures and their online analogues have come to appear (once again) quaint.

(iii) From closed systems, or recycled human excreta, to undomesticated ejecta

In Bataillean terms, the twin hypotheses introduced above invite differential responses. If generative AI is genuinely excessive in the first sense, in that it is prodigiously wasteful, generative AI might be less of a worry from the perspective of Bataille’s general economy (where pent-up energies are considered far more concerning). However, if AI is driven to consume and circumscribe or cast out and annul its own excess in the second sense, the consequences are considered to be rather more serious. That is to say, if generative AI maintains the kind of ascendancy that many critics predict and fear, this raises the question of whether or not human excess (formerly a kind of waste effect, or unusable biproduct of human activity) will itself be more or less fully enclosed by the algorithmic circuit. This prospect certainly does seem conceivable to the extent human activity is recorded or leaves a trace (as most human activities now do), so that any human utterance, any fumbled comment or act can be used as AI training material. There is the prospect, in other words, of a digital culture which has entirely surrounded and instrumentalised human activity.

Andrew C. Wenaus has phrased this in textual terms appropriate to the new “psycho-ecology” that is being entered here. Wenaus asks if this shift to a digitised, algorithmically mediated future, might lead to “a closed system that eschews poiesis”, where the word poiesis is meant in the broad sense of creating new ideas, novel concepts. It is worth asking with Wenaus if the proliferation of AI might already be “delimiting the unpredictable emergence of novel potencies and unruly potentialities, both useful and useless” by favouring the probabilistic, and before that, by only considering what can be rendered as data. The consequences for human agency might be profound. In linguistic terms, this announces a period in which “the more one nonhabitually engages with unusual modes of language, the more one may exercise agency” (Wenaus The Literature of Exclusion 2). Heterodox expression only becomes more important in a computational context that frames the linguistic environment within which actors perceive, move and express.

This, then, is how the question of whether or not AI represents a curtailment of human (and non-human) possibility might be put. And in a manner that is not mutually exclusive, it might be asked if the eventual survival (the future viability) of AI as a creative force may itself not benefit, curiously enough, from the degree of chaos and unpredictability that its users are capable of injecting. This would be a disruptive endeavour that would extend far beyond the above cited aim to merely protect the ‘outliers’ in the distribution so as to ensure the ‘richness’ of the data, a commitment which seems to be yet another way of celebrating ‘human diversity’ in a social system that does not wish to perturb the majority, the norm, or the dominant group. Clearly the task envisaged here is for more than a few oddballs or innovators, the pet projects of the rich and benevolent, those who would be permitted to work on their artistic and literary projects whilst in receipt of public grants, bursaries, or merely permissions. If the second hypothesis holds, and generative AI establishes itself as a greedy aggregator, as a totalising regime for the absorption and re-deployment of excess (within and by way of its data centres initially until other means may be found), then it is worth wondering how AI might be more deliberately punctured. If co-option is the major concern, the question becomes one of how AI-enclosure might be perhaps exceeded by excessive, irrecuperable acts. Arguably, generative AI already provides the field of contestation in the terms of obsolescence, over the multiple domains of obsolescence-production and obsolescence-avoidance discussed in Part One. In such a context, these irrecuperable acts might be oriented towards the (perhaps unrealisable) aim of ‘immediate obsolescence’. They would be obsolete on arrival, meaning, they would be enacted in such a way that they could not be incorporated as training material. It should come as no surprise to state that it is impossible to envisage how these acts might look or how actors might need to strategize in order to remain beyond reach. But it is likely these acts might draw resource from the very faculties that technologies have hooked themselves into, where “the apparatus embeds itself in the unconscious, it thrives on the infinite libidinal and irrational flows of emotive, addicted, and reactionary psychic automatisms”, the comforts and minor thrills of the smartphone or watch (Wenaus The Literature of Exclusion 18). The very same irrational drives might be exploited against the apparatus and perhaps by way of it, erupting against its habitual behaviours and social reflexes. This is a somewhat counter-intuitive proposal—or a proposal that can only be made at the price of its own confusion—given that it is placed on the side of the unusable excess, the waste material of human activity which can be identified only to the extent that it is not yet worth anything, to the extent it can still escape instrumental use, and remains for that reason, somewhat excremental.

Certainly, all the output that AI produces and reabsorbs will not be opposed here to so-called authentic textual outputs, those which recall the long centuries before generative AI took hold of language and apparently discredited it. Rather, new forms of inauthenticity, or infidelity, might be sought after instead. The predicament bears analogy to the North Korean response to the propaganda, the leaflets and pen drives, or what it called the “dirty things” that were sent from South Korea by activists who have defended their right to do so in court as a matter of free speech (the right to visit their own ‘truths’ upon the north). The regime sent its own reply, a fleet of balloons to drop refuse including excrement south of the border (Sharma). This reply ducked out of a rational discourse of apparently free and truthful exchange, of oppositional but mannered argument, of cultivating environments where thought is apparently not distorted by irrational forces and debased impulses. It returned the debate between North and South to a question of deployment and counter-deployment, insult and counter-insult. By extension, an approach to the problem of generative AI which asks how texts and human energies might be better dispensed with, does not seek to maintain truth against lies, rectitude against filth, or psychological depth or humanity against its simulation. It considers the uncertain zone where so-called actuality meets its fabricated other and where it is hard to tell the difference, as a space worth investigating, perhaps a place, a zone, to venture into, transect, inhabit. There might be better ways of lying, committing error, or introducing fakery, of which AI is merely the least gainful, most predictable variant.

(iv) Gambits for the expenditure of texts

Extraordinary access to cultural texts, legitimately shared and ‘liberated’, has brought the library, the gallery, and the museum into the device. The effects have not been particularly humanising, or enlightening, at least not on a scale to match the scale of availability. Mere access to resource, to the full gamut of human thought, will not offset global stupidity… These would be the complaints of a humanist outlook which would observe that habits of reading and appreciation must be taught, and a circulation of texts in itself will never ennoble or instruct.

In the context of so much circulating data, old humanist methods of acculturation must surely come to appear obsolete themselves, just as older systems of cultural servitude, such as ‘politeness’ have long been under attack, “be it the politeness of the arts, known as “taste”; that of the brain, referred to as “intelligence”; that of daily life, which we designate by a word… “morality’” (Leiris 94). Michel Leiris was here bemoaning politeness at a time (the late 1920s) when respectability had its restraining hooks fairly well driven in. In the mid 2020s, politeness is no longer the chief constraint when impropriety inhabits the algorithm and theft reigns. By extension, the absorption of a vast textual resource by the internet scrapers which feed generative AI might be owed an appropriately belligerent artistic response. It would give up the last residues of an old, humanist-scholarly respect for the integrity of texts. These texts have, after all, already been torn from their physical selves and their reading cultures. They have been utterly disrespected already.

Leiris, like Bataille, had in mind an experience which stepped outside of its time, framing his interest in primitive culture (somewhat bombastically) as a consequence of having “so little respect remaining for anything that does not annihilate the succession of centuries in one stroke and put us, stripped naked, in a more immediate and newer world” (Leiris 94). The body is to be given prominence so that it may disturb the operations of the individuated consciousness. Its emissions and natural processes are invoked for their capacity to expand human thought and action from those spaces it has retreated to. This should not be read as a retreat to animality or animal immediacy—the human intellect is still not yet dispensed with. As Bataille writes, animality is “something we see every day in the activity of dogs, in which we have a spectacle which is literally terrifying”—it would be a frightful, comedic, “powerless martyrdom” (Bataille The Absence of Myth 89).

Rather, an expenditure of texts might take the form of a practical and embodied revolt, less concerned to bring disgrace on its materials, more interested in seeing what they might do. It is an individual and communal refusal of what is given, of what is presented as given, a refusal that is also an eruption of new possibilities. Its irreverent textual-artistic practices do not remain at the stage of formal innovation. Their deployment coincides with an expenditure of life and resource. Those engaged seek to expend or give up those selves which have accreted in an otherwise moribund political moment. Their work rides on the intuition that there is an art to fabrication, fecundity in error, and generative potential in lies.

Critical and embodied fabricators might invent to evade capture—fabricating texts from other texts, neither straight fictions nor attempts to uncover or at least show respect for the integrity of the original. This confounds power, to the extent power still operates by classifying, locating, and immobilising, a process that includes all the psychological and inter-relational work that goes into attaching individuals to their identities.

Today’s great plagiarists—algorithms trained on vast datasets—raid their libraries with so little restraint because they cannot become glutted, backed up, or bored. A power to assimilate, mix, and churn out text has been unleashed that no human reader can rival, but it lacks materiality, and not in the sense that it cannot be materialised (for it surely can), but in the sense that its thinking is not planted in the muck or connected to a body that is restrained as it is driven by its limitations.

Embodied fabricators have less consumptive avidity. Even if they augment their work by forming partnerships with generative AI, these fabricators introduce a lag within computational immediacy. Their very shortcomings, their bodies and attendant psychologies, bring discord and distraction to their reading. These fabricators lean with their flesh as well as their intellect into what Bataille had in mind when he sought to outline the features “of a “general economy” in which the “expenditure” (the “consumption”) of wealth, rather than production, was the primary object” (Bataille The Accursed Share, Vol.I 9). Wealth, in their case, is expended in its laboured textual form and it is largely done fruitlessly—there are few admirers for this kind of work. But it is also expended in the very drag that embodied fabricators entrain—wealth is squandered as time and as failure to write. The impulse to inscribe is given over to unproductive making, to the creation of new, potentially even more worthless outputs. These are worthless because they are unclassifiable, or not-yet-marketable, or have an indeterminate status. And they remain excessive insofar as meaning cannot be finally determined and time spent cannot fully be accounted for. Fabricants are themselves open to an extraordinary prospect of redeployment and rearticulation. Their fecundity is their obsolescence is their crime against closure.

[Ansgar Allen]

References:

Adam, David. “Lethal Ai Weapons Are Here: How Can We Control Them?” Nature 23 April 2024. Print.

Alexander, Alistair. “After Progress: Is Artificial Intelligence Degenerating Human Knowledge?” Berliner Gazette 14 February 2025. Print.

Arielli, Emanuele. “Ai-Aesthetics and the Artificial Author.” Proceedings of the European Society of Aesthetics 15 (2023): 40-54. Print.

Armand, Louis. “Postludes: Cinema at the End of the World.” Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 22.3 (2017): 155-63. Print.

Balasubramanian, Sivasubramanian, et al. “Ethical Considerations in Ai-Assisted Decision- Making for End-of-Life Care in Healthcare.” Power System Technology 47.4 (2023). Print.

Bales, Adam. “Ai Takeover and Human Disempowerment.” The Philosophical Quarterly (forthcoming). Print.

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” Trans. Heath, Stephen. Image, Music, Text. London, UK: Fontana, 1987 [1968]. Print.

Bataille, Georges. The Absence of Myth: Writings on Surrealism. Trans. Richardson, Michael. London, UK: Verso, 1994. Print.

---. The Accursed Share, Volume I. Trans. Hurley, Robert. Brooklyn, NY: Zone Books, 2022 [1967]. Print.

---. The Limit of the Useful. Trans. Knudson, Cory Austin and Tomas Elliot. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022 [1976]. Print.

Bedingfield, Will. “Hollywood Writers Reached an Ai Deal That Will Rewrite History.” Wired 27 September 2023. Print.

Benjamin, Walter. “One-Way Street.” Trans. Underwood, J. A. One-Way Street and Other Writings. London, UK: Penguin, 2009 [1928]. Print.

Blum, Sam. “Scale Ai Sued for Subjecting Contract Workers to ‘Depraved’ Content.” Inc. 23 January 2025. Print.

Booten, Kyle. “Flusser’s Demon: Writing under the Eye of an Automatic Critic.” Flusser Studies 30 (2020). Print.

---. “Lotus Chorus Workshop: Designing for Cognitive Overload.” xCoAx (2023). Print.

Breton, André. Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism. Trans. Polizzotti, Mark. New York, NY: Marlowe & Company, 1993 [1969]. Print.

---. “Manifesto of Surrealism.” Trans. Seaver, Richard and Helen R. Lane. Maniestoes of Surrealism. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1972 [1924]. Print.

Bruni, Frank. “Will Chatgpt Make Me Irrelevant?” The New York Times 15 December 2022. Print.

Bucknall, Benjamin S., and Shiri Dori-Hacohen. “Current and near-Term Ai as a Potential Existential Risk Factor.” AIES ’22. 2022. Print.

Castelvecchi, Davide. “Are Chatgpt and Alphacode Going to Replace Programmers?” Nature 8 December 2022. Print.

Chatterjee, Mohar, and Madison Fernandez. “‘An Arms Race Forever’ as Ai Outpaces Election Law.” Politico 2 July 2024. Print.

Chow, Andrew R., and Billy Perrigo. “The Ai Arms Race Is Changing Everything.” Time 16 February 2023. Print.

Christchurch, Mark. “I Asked Chat Gpt to Write a Song in the Style of Nick Cave and This Is What It Produced.” January 2023. Print.

Christian, Brian. The Alignment Problem: How Can Artificial Intelligence Learn Human Values? New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020. Print.

Coeckelbergh, Mark, and David J. Gunkel. “Chatgpt: Deconstructing the Debate and Moving It Forward.” AI & Society 39 (2024): 2221–31. Print.

Cremer, David De, Nicola Morini Bianzino, and Ben Falk. “How Generative Ai Could Disrupt Creative Work.” Harvard Business Review 13 April 2023. Print.

Crosthwaite, Paul. “Blood on the Trading Floor: Waste, Sacrifice, and Death in Financial Crises. .” Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 15.2 (2010): 3-18. Print.

D’Amato, Kristian. “Chatgpt: Towards Ai Subjectivity.” AI & Society 40 (2025): 1627–41. Print.

Demmer, Theresa Rahel, et al. “Does an Emotional Connection to Art Really Require a Human Artist? Emotion and Intentionality Responses to Ai- Versus Human-Created Art and Impact on Aesthetic Experience.” Computers in Human Behaviour 148 (2023). Print.

DeVon, Cheyenne. “There’s ‘No Way’ Ai Will Completely Replace Human Musicians, Says Award-Winning Composer—Here’s Why.” CNBC 29 December 2023. Print.

Dung, Leonard. “The Argument for near-Term Human Disempowerment through Ai.” AI & Society 40.3 (2025): 1195–208. Print.

Dzieza, Josh. “Ai Is a Lot of Work.” The Verge 20 June 2023. Print.

Emerson, Sarah, and Richard Nieva. “Eric Schmidt Is Secretly Testing Ai Military Drones in a Wealthy Silicon Valley Suburb.” Forbes 6 June 2024. Print.

Etzioni, Amitai, and Oren Etzioni. “Designing Ai Systems That Obey Our Laws and Values.” Communications of the ACM 59.9 (2016). Print.

Fabrocini, Filippo, Kostas Terzidis, and De’en Chen. “Finally, the Death of the Author! A ‘Detournement’ Strategy for Decolonizing the Artistic Venue.” AI & Society 40.4 (2025): 2171-79. Print.

Floridi, Luciano. “Ai as Agency without Intelligence: On Chatgpt, Large Language Models, and Other Generative Models.” Philosophy & Technology 36.15 (2023). Print.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Trans. Sheridan, Alan. London: Penguin, 1975 [1991]. Print.

---. “What Is an Author?” Trans. Harari, Josué V. and Robert Hurley. Essential Works of Foucault 1954-1984. Volume 2. Ed. Faubion, James. Vol. 2. London, UK: Penguin, 2000 [1969]. Print.

---. The Will to Knowledge. Trans. Hurley, Robert. London, UK: Penguin, 1998 [1976]. Print.

Habgood-Coote, Joshua. “Deepfakes and the Epistemic Apocalypse.” Synthese 201.103 (2023). Print.

Han, Shengnan, et al. “Aligning Artificial Intelligence with Human Values: Reflections from a Phenomenological Perspective.” AI & Society 37 (2022). Print.

Hawkins, Harriet. “Visions of Excess: Michael Landy’s Break Down and the Work of George Bataille.” Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 15.2 (2010): 19-37. Print.

Huling, Ray. “Bataillean Ecology: An Introduction to the Theory of Sustainable Excess.” Moveable Type 11 (2019): 25-37. Print.

Hutson, James, and Ana Schnellmann. “The Poetry of Prompts: The Collaborative Role of Generative Artificial Intelligence in the Creation of Poetry and the Anxiety of Machine Influence.” Global Journal of Computer Science and Technology: D Neural & Artificial Intelligence 23.1 (2023). Print.

Jones, Nicola. “The Ai Revolution Is Running out of Data. What Can Researchers Do?” Nature 11 December 2024. Print.

Kasirzadeh, Atoosa, and Iason Gabriel. “In Conversation with Artificial Intelligence: Aligning Language Models with Human Values.” Philosophy & Technology 36.27 (2023). Print.

Keating, Joshua. “Why the Pentagon Wants to Build Thousands of Easily Replaceable, Ai-Enabled Drones.” Vox 22 March 2024. Print.

Kendall, Stuart. “Making More (of Waste).” Georges Bataille and Contemporary Thought. Ed. Stronge, Will. London, UK: Bloomsbury, 2017. Print.

Lee, Hye-Kyung. “Reflecting on Cultural Labour in the Time of Ai.” Media, Culture & Society 46.6 (2024): 1312-23. Print.

Leiris, Michel. “Civilization.” Trans. White, Iain. Encyclopaedia Acephalica. Ed. Brotchie, Alastair. London, UK: Atlas Press, 1995 [1929]. Print.

Levy-Landesberg, Hadar, and Xuenan Cao. “Anchoring Voices: The News Anchor’s Voice in China from Television to Ai.” Media, Culture & Society 47.2 (2025): 229-51. Print.

Lyu, Siwei. “Deepfakes and the New Ai-Generated Fake Media Creation-Detection Arms Race.” Scientific American 20 July 2020. Print.

Manghani, Sunil. “Model Collapse: When Ai Eats Itself….” Medium 20 November 2023. Print.

Mbembe, Achille. Necropolitics. Trans. Corcoran, S. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019 [2016]. Print.

McGoey, Linsey. “Bataille and the Sociology of Abundance: Reassessing Gifts, Debt and Economic Excess.” Theory, Culture & Society 35.3-4 (2018): 69-91. Print.

McKernan, Bethan, and Harry Davies. “‘The Machine Did It Coldly’: Israel Used Ai to Identify 37,000 Hamas Targets.” The Guardian 3 April 2024. Print.

McQuillan, Dan. Resisting Ai: An Anti-Fascist Approach to Artificial Intelligence. Bristol, UK: Bristol University Press, 2022. Print.

Milman, Oliver. “Ai Likely to Increase Energy Use and Accelerate Climate Misinformation – Report.” The Guardian 7 March 2024. Print.

Monteith, Scott, et al. “Artificial Intelligence and Increasing Misinformation.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 224.2 (2024). Print.

Munn, Luke, Liam Magee, and Vanicka Arora. “Truth Machines: Synthesizing Veracity in Ai Language Models.” AI & Society 39 (2024): 2759–73. Print.

Paul, Kari. “Letter Signed by Elon Musk Demanding Ai Research Pause Sparks Controversy.” The Guardian 1 April 2023. Print.

Perrigo, Billy. “Exclusive: Openai Used Kenyan Workers on Less Than $2 Per Hour to Make Chatgpt Less Toxic.” Time 18 January 2023. Print.

Peterson, Andrew J. “Ai and the Problem of Knowledge Collapse.” AI & Society 40.5 (2025): 3249–69. Print.

Quach, Katyanna. “Researchers Made an Openai Gpt-3 Medical Chatbot as an Experiment. It Told a Mock Patient to Kill Themselves.” 28 October 2020. Print.

Rao, Rahul. “Ai-Generated Data Can Poison Future Ai Models.” Scientific American 28 July 2023. Print.

Reich, James. Skinship. Grand Rapids, MI: Anti-Oedipus Press, 2024. Print.

Ricaurte, Paola. “Ethics for the Majority World: Ai and the Question of Violence at Scale.” Media, Culture & Society 44.4 (2022): 726-45. Print.

Sharma, Shweta. “North Korea Drops Balloons Full of Rubbish and Excrement onto South Korea.” The Guardian 29 May 2024. Print.

Shumailov, Ilia, et al. “Ai Models Collapse When Trained on Recursively Generated Data.” Nature 631 (2024): 755–59. Print.

Söffner, Jan. “Virtualism: How Ai Replaces Reality.” AI & Society 40.3 (2025): 1389–401. Print.

Stening, Tanner. “How One Philosopher Is Thinking About the Problem of Deepfakes, Ai and the ‘Arms Race’ to Rein in Deception Online.” NGN Magazine 12 February 2024. Print.

Stoekl, Allan. Bataille’s Peak: Energy, Religion, and Postsustainability. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2017. Print.

Taher, Hassan. “The Arms Race in Artificial Intelligence: Combating Deepfakes.” Medium 29 August 2023. Print.

Vachnadze, Giorgi. “Biopolitics and Ai: Deskilling as a Disciplinary Political Technology.” Berline Gazette 8 January 2025. Print.

Veltman, Chloe. “Thousands of Authors Urge Ai Companies to Stop Using Work without Permission.” NPR 17 July 2023. Print.

Wenaus, Andrew C. “An Interview on the Crafting of the Infinite Metalanguage.” Ed. Kogkas, Spyridon-Stefan. Thrausma2024. Print.

---. The Literature of Exclusion: Dada, Data, and the Threshold of Electronic Literature. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2021. Print.

Williams, Henry. “I’m a Copywriter. I’m Pretty Sure Artificial Intelligence Is Going to Take My Job.” The Guardian 24 January 2023. Print.

Winter, Joost de, P. A. Hancock, and Yke Bauke Eisma. “Chatgpt and Academic Work: New Psychological Phenomena.” AI & Society 40.6 (2025): 4855–68. Print.

Yadlin, Aya, and Avi Marciano. “Hallucinating a Political Future: Global Press Coverage of Human and Post-Human Abilities in Chatgpt Applications.” Media, Culture & Society 46.8 (2024): 1580-98. Print.